The History of Provincetown-Boston Airline, Inc.

Preface

In today’s commonplace practice of code sharing, regional airlines are evermore losing their corporate identities. While such names as Aspen, Henson and Empire once graced America’s airports, today’s regional airlines lack a true sense of recognition, choosing instead the generic umbrella of the likes of United Express, Delta Connection or American Eagle. However, there is one regional airline in particular which will forever stand out among the masses.

A pioneer of the commuter airline industry, Provincetown-Boston Airline (PBA) grew out of humble beginnings to become the industry’s largest and leading regional carrier — only to meet its downfall like the mythological character, Icarus, whose wings melted having flown too closely to the sun. Yet, to this day PBA still receives the love, admiration and respect from former rivals, passengers and employees alike.

Humble Beginnings

Having been raised the son of a pilot, John Van Arsdale Sr. had a passion for aviation — so much in fact, that he overcame bouts of airsickness in acquiring his pilot’s license. Yet, in addition to his love of flying, Van Arsdale — affectionately known as “Old Man Van” — was also gifted with a keen hindsight, for he believed civilian aviation to be the business opportunity of the future.

Upon the completion of World War II, Van Arsdale returned to the sandy peninsula of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the place where he had spent many boyhood summers vacationing with his family. There he approached Mrs. W. H. Danforth, an old family friend and proprietor of the Cape Cod Airport located in Marstons Mills, Massachusetts. During this encounter Van Arsdale proposed the idea of owning and operating a flying school at Danforth’s establishment. In turn, a lease agreement was reached in which Van Arsdale, in addition to managing his flying school, would also be responsible for running the airport’s operations.

Having performed extensive repairs to the 365-acre facility (i.e., filling in holes in the runway), Van Arsdale’s dream soon became a reality. With a fleet of two new J-3 Piper Cubs and a war surplus Stearman PT-17, the Cape Cod Flying Service officially opened on May 8, 1946.

Shortly afterward Lady Luck smiled on Van Arsdale. With the passing of the G.I. Bill the Veterans Administration appointed the Cape Cod Flying Service as the first accredited school qualified to train veterans in Massachusetts. Immediately Van Arsdale began hiring the best instructors as veterans from all over soon flocked to the school. In fact, Van Arsdale even enrolled himself in the institution, which always made for lighthearted conversation. Indeed, Old Man Van loved to brag how he gained his commercial license — by training at his own school — and how it was all paid for under the G.I. Bill.

Opportunity Knocks

Two years later good fortune again intervened on Van Arsdale’s behalf, as leaders from the nearby community of Provincetown, Massachusetts, requested that he open a similar venue at the town’s new airport. Sensing a great opportunity, as well as realizing the G.I. Bill would not last forever, Van Arsdale seized the moment. Though the Provincetown Municipal Airport officially opened on Oct. 19, 1948, a double ceremony was held at the facility on Oct. 31: one celebration commemorated the airport’s grand opening, while the other marked the debut of the field’s first tenant, the (newly relocated) Cape Cod Flying Service.

In addition to being proprietor of the flying school, Van Arsdale also assumed the role of airport manager. Hence, as was the case in Marstons Mills, his everyday duties included such tasks as pumping fuel, renting out space and giving flying lessons — an overall experience that would play a major determinate in PBA’s future.

Shortly after opening for business, however, Van Arsdale became inundated with requests for air taxi charters between Provincetown and the city of Boston. While the typical trek called for a then five-hour, 120-mile excursion over land, this journey could now be completed in under 30 minutes by air. Needless to say, Van Arsdale’s alternative quickly became a popular mode of transportation.

Likewise, it was also during this period that Old Man Van began incorporating a new plan of operation — one destined to become a PBA trademark: optimize a mixed fleet of aircraft to correspond with passenger demand. Under this strategy each aircraft would be utilized to its maximum potential, thus avoiding a waste in costs brought on by overcapacity. With an initial fleet of three, single-engine aircraft, Van Arsdale began matching the requested charters as follows: a Cessna 140 for one passenger, a Piper Clipper for two passengers and a Stinson Voyager for three passengers.

With the demand for charter services continuing to escalate, Old Man Van petitioned to begin regularly scheduled service on the Provincetown–Boston run. Sensing government approval of his application, Van Arsdale quickly leaped into action. First came the need for a new, larger capacity aircraft — one that would not only accommodate the demand, but also offer greater comfort and reliability. In turn, a four-passenger, twin-engined Cessna T-50 Bobcat (commonly known as the “Bamboo Bomber”) was acquired.

As a matter of reference, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) did not recognize “commuter” airlines until the late 1960s. However, according to R.E.G. Davies’ authoritative tome, Commuter Airlines of the United States, PBA “was recognized by its peers as the prototype of what were known first as scheduled air taxi operators, then as third level carriers, and later as commuter airlines, before adopting … the somewhat vague designation of regional airlines.”

“The Route of the Pilgrims”

On Nov. 30, 1949, PBA’s maiden flight — touting a fully loaded Cessna Bobcat — departed Provincetown promptly at 9 a.m., arriving at Boston’s Logan Airport 25 minutes later.

Subsequently, scheduled services — dubbed “The Route of the Pilgrims” — consisted of twice-daily roundtrips between the two New England cities. In a 1949 interview with the Boston Daily Globe, Van Arsdale stated that “the airline had adopted the slogan, ‘The Route of the Pilgrims,’ as the approved route of the flights is from Provincetown to Plymouth Harbor and then north to Boston, the same as that of the Pilgrims … when they left Provincetown for Plymouth, and ultimately many of them to Boston.”

With a one-way fare of $6.95 (plus tax), the carrier soon became a successful venture. In fact, having boarded 2,495 passengers in its first year, PBA marked the beginning of 35 consecutive years of profitability.

All In The Family

When describing the early days of PBA the phrase “mom-and-pop” operation immediately comes to mind. With the airline’s initial success Van Arsdale quickly moved his family to Provincetown in order to assist with the business. There, Mom Betty Van Arsdale ran the office, while Pop Van Arsdale piloted the planes, and daughter Jean assisted in the ticket office.

Though Jean was not particularly interested in flying, the same could not be said, however, for brothers John Jr., Peter and Bill, who all began working as assistant linemen (i.e., baggage handling, vacuuming out airplanes, cleaning up around the field, etc.) by age 12. Upon turning 14 each boy was taught how to fly by none other than Old Man Van himself. By age 16 each son had soloed, and at 17 had received his private license. By age 18 all three sons had acquired his commercial license having earned his wings in the same Piper Cub with which their father began the Cape Cod Flying Service.

From The A J Jackson Collection at Brooklands Museum.

By 1952 success had brought forth two new aircraft to PBA’s fleet: an additional Cessna Bobcat and a 10-passenger Lockheed 10-A Electra. Furthermore, 1952 also marked the year of the airline’s incorporation. While originally a subsidiary of the Cape Cod Flying Service, PBA was now established under its own identity — Provincetown-Boston Airline, Inc.

Two years later fate once again smiled on Van Arsdale’s behalf. Having lobbied the government for several years, PBA was finally granted an “Air Star Route” between Provincetown and Boston. Under an agreement with the U.S. Postal Service — a rare and lucrative venture for the time — Van Arsdale contracted to shuttle air and first-class mail between July 1 and Sept. 15 — the peak of the summer tourist season. Utilizing the Lockheed Electra, PBA’s Air Star Route initiated service on July 19, 1954.

With A Little Help From His Friend

Though financially sound since its inception, PBA’s seasonal service always presented an unequivocal dilemma: both the airline’s fleet and personnel were being underutilized during the winter off-season. In an attempt at resolving this problem, Van Arsdale and his wife traveled to the state of Florida, also renown for its tourist industry.

Albeit seasonal in nature, Van Arsdale found the Florida market to be most appealing, for the state’s tourist season was totally opposite to the one in New England. Thus, while the tourist trade flourished during the summer months up North, Florida became a haven for vacationers during the winter — in essence, an ideal scenario for keeping PBA productive on a yearly basis.

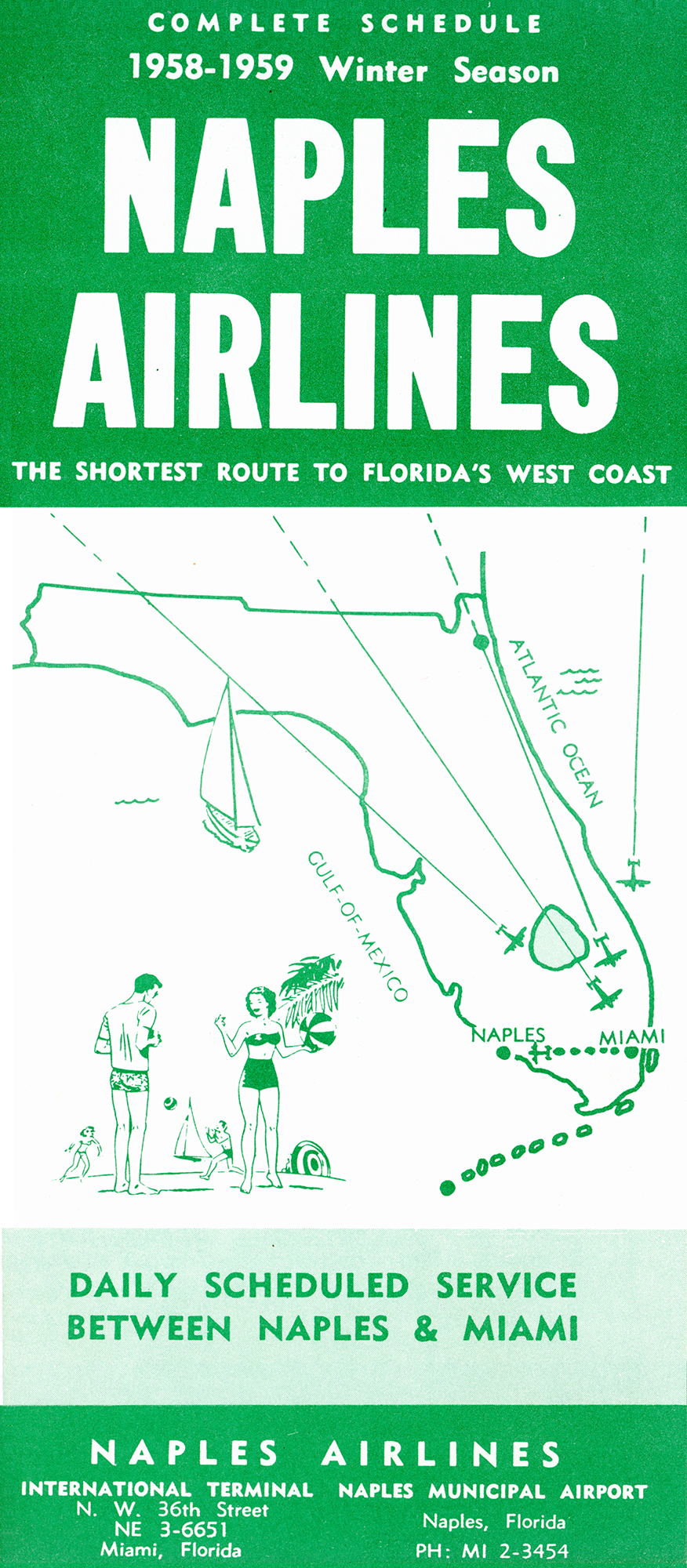

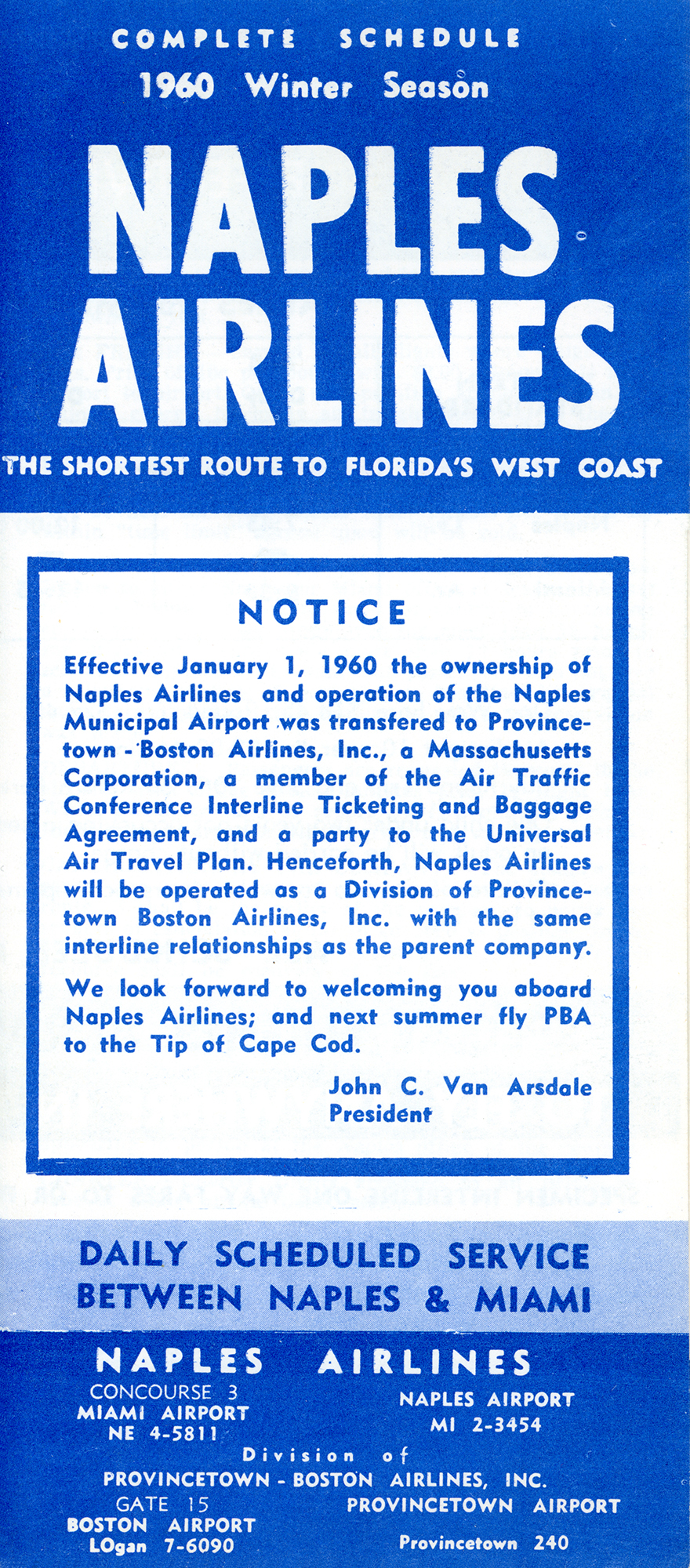

Shortly after arriving in the Sunshine State, the Van Arsdales made their way to the Gulf Coast community of Naples, located in Southwest Florida. There they came across a gentleman named Joseph L. Brown, the founder and proprietor of Naples Airlines.

Launched in 1955 as Naples Air Service, Naples Airlines operated twice daily scheduled service, provided on a seasonal basis, between Naples and Miami. Moreover, the carrier’s owner, like Van Arsdale, was confronted with keeping his operation — a four-passenger Cessna 195, a nine-passenger Beech 18 and a 10-passenger Lockheed 10-A Electra — productive during seasonally slow periods.

Sensing a window of opportunity, Old Man Van proposed the idea of exchanging equipment and employees in response to seasonal demand. Simply put, a portion of PBA’s fleet and personnel would be sent to bolster Naples Airlines during the winter, and likewise, Naples would send similar support to Massachusetts during the summer. Having agreed to this arrangement, mutual services began on Dec. 15, 1957.

Partnership Woes

While PBA continually operated in a prosperous manner, the same could not be said, however, for its Southern counterpart. By the fall of 1959, Naples Airlines was facing such insurmountable debt that Brown ultimately placed the airline up for sale. In turn, Van Arsdale, having foreseen Naples Airlines’ potential, submitted a bid against 14 other operators for the right to procure the floundering airline.

In determining the carrier’s new owner, the Naples City Council, still enraged over Naples Airlines’ unpaid debt, demanded that the selected bidder be the one with the highest qualifications and not necessarily the highest bid. Since an airport lease agreement was mandatory for any airline wishing to serve Naples, the City felt obligated to render its opinion in the selection process. In turn, a compromise was struck. While Brown would receive payment for the airline, the Naples City Council would select the carrier’s new owner.

Naples Airlines Climbs Aboard

In approving Brown’s successor the City weighed in with the following criteria: One stipulation involved the frequency of service — a minimum of two daily roundtrips between Naples and Miami, provided on a seasonal basis. While a second stipulation required that the airline’s new owner be responsible for running the Naples Municipal Airport.

Having proven success in managing both an airline and not one, but two airports, Van Arsdale — while not the highest bidder — was undoubtedly the most qualified candidate. Consequently, Old Man Van was awarded the airline on Dec. 31, 1959, and on New Year’s Day, 1960, Naples Airlines was officially designated a division of Provincetown-Boston Airline, Inc.

Under the auspices of Van Arsdale the Naples carrier inaugurated service on Feb. 1, 1960, operating three daily roundtrips between Naples and Miami. Hereafter, regular services were conducted between mid-December and mid-April.

Though having merged the assets of Naples Airlines with those of PBA, Van Arsdale continued to operate the two carriers as separate entities, thus preserving Naples’ identity and name recognition. Interestingly, in keeping with the name recognition philosophy, those aircraft destined for use in both Florida and Massachusetts reflected a new and rather distinctive title: “Naples Airlines & Provincetown-Boston Airline.” Yet, as Van Arsdale ushered in the decade on a positive note, little did he know of the magnitude of this newest acquisition.

In the years shortly thereafter, the newfound success of Naples Airlines led to the addition of three, five-passenger Piper Apaches to the carrier’s fleet. Furthermore, by early 1964, Florida’s volume of traffic had surpassed that in New England; thus, Van Arsdale’s center of focus had now shifted toward the Sunshine State. Indeed, the Naples–Miami route had become so successful that daily, year-round service was initiated later that same year.

Now Arriving: The DC-3 & “The Tampa Connection”

By the onset of 1968, Naples prosperity had finally reached a point. Faced with overwhelming load factors, Old Man Van began searching the market for larger capacity aircraft. On Feb. 29, the search concluded with the purchase of two Douglas DC-3s. Acquired from Modern Air Transport, both aircraft were configured to accommodate 32 passengers, thus tripling the capacity of the Lockheed Electras being replaced. With Vice President John E. Zate at the helm and Old Man Van acting as cabin attendant, Naples Airlines inaugurated DC-3 service to Miami on March 22, 1968.

In selecting the Douglas classics, however, Old Man Van had also envisioned their use in a planned expansion of the Florida market, in which the carrier’s third hub operation — similar to those in Boston and Miami — would be established. In turn, the city of Tampa, Florida, was selected as Naples Airlines’ newest gateway, with roundtrip service between Naples and Tampa commencing on June 1, 1968.

Though this latest effort initially resulted in moderate success, the situation dramatically changed with the unveiling of Tampa International Airport’s unprecedented terminal in the spring of 1971. With the lure and appeal of a spectacular new facility, passengers soon chose the “Tampa Connection” as the airline’s preferred hub destination. In turn, the Naples–Tampa city pair quickly established itself as the leading market in the PBA/Naples Airlines system.

Heir Apparent

From the time of PBA’s inception Old Man Van had always owned 100 percent of the company. However, in 1974 he startled everyone in the organization by distributing corporate shares among family members. While still maintaining controlling interest in the company, Van Arsdale allocated the greatest percentage of stock to sons John Jr. and Peter, who each received equal (29) shares.

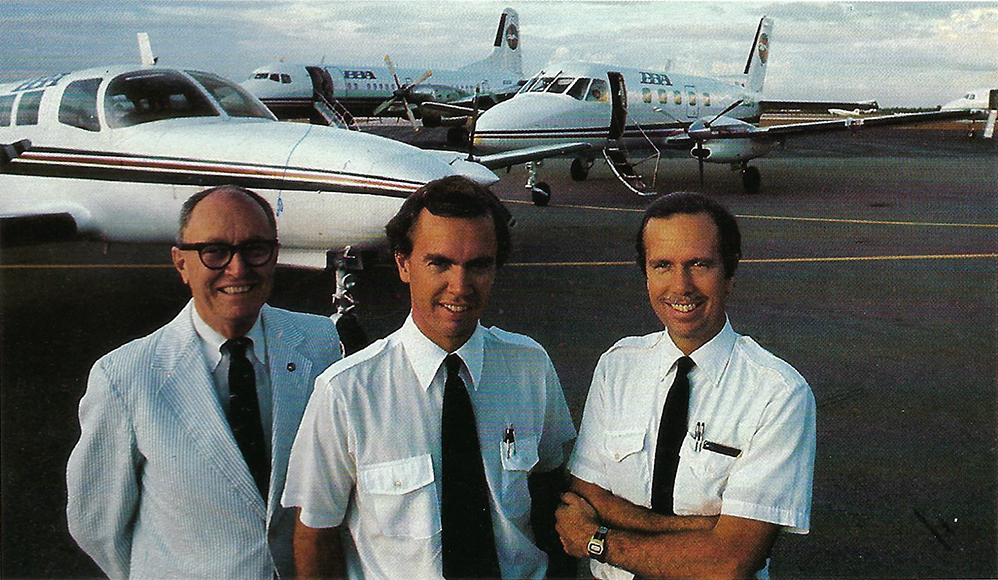

While new at being PBA stockholders, John Jr. and Peter Van Arsdale were by no means strangers to the organization. Since becoming assistant linemen at age 12, the Van Arsdale boys had always been part of the company. “They had no choice,” Old Man Van once jokingly remarked. Though youngest brother Bill went on to pursue his own aspirations, the two older siblings each took different roads before settling in at PBA.

After receiving his bachelor’s degree in economics, John Jr., the eldest brother, spent the next two years piloting for PBA before being drafted into the U.S. Marine Corps in 1969. Following a two-year stint as an accountant, he returned to civilian life and immediately began seeking employment as a pilot for an international airline. Upon finding no such openings he returned to PBA where he resumed piloting on a full-time basis. In 1972 he eventually joined the ranks of management, having been appointed vice president of administration. However, this did not spell the end of his flying days, for company policy required that members of upper management also be certified pilots. Therefore, he assumed the dual role of both pilot and administrator.

Upon earning his engineering degree in 1971, middle brother Peter also returned to pilot for PBA. However, in the summer of 1972 he decided to leave the airline in search of a banking career in California. Having been unsuccessful in his quest, Peter returned to PBA where, two years later, he attained the position of assistant vice president — in addition to maintaining his duties as a pilot. Thus, by 1974 Old Man Van had established his heir successors to the company.

In addition, 1974 also marked the unveiling of the carrier’s newest fleet acquisition, the Cessna 402. Inevitably, these nine-passenger twins would become the backbone of PBA’s operation.

Martinliners to the Rescue

Having boarded 114,110 passengers throughout the following year, 1975, the CAB recognized Naples Airlines as the 13th busiest commuter airline in the nation — this, out of a field of 213 carriers. In addition, Naples also went on to receive its highest distinction: the Air Transport World Award as the 1975 Commuter Airline of the Year.

While undoubtedly proud of these recent accolades, management had no time to spend resting on its laurels. As the load factors at PBA/Naples Airlines became ever increasing, Old Man Van began contemplating yet another addition to the fleet. In a memorandum dated Jan. 15, 1976, Van Arsdale used the following to illustrate the need for extra capacity: On Jan. 4, 1976, Naples Airlines — using six DC-3s and a five-passenger Piper Aztec — transported 197 passengers to Tampa at 10:15 a.m. One hour later the airline then carried 84 passengers to Miami, and still another 185 passengers to Tampa at 12:30 p.m. Therefore, in response to this tremendous, yet common display of growth, four, 44-passenger Martin 4-0-4s were acquired from Southeast Airlines. Sporting the NAPLES moniker on its fuselage and the PBA logo on its tail, the Martin 4-0-4 debuted on the Naples–Tampa run effective April 16, 1976.

Throughout the remaining decade Van Arsdale continued to run the airline in his typically conservative manner. However, in October 1977, Naples Airlines did initiate service to the Florida community of Punta Gorda, the carrier’s first new destination in nine years.

The Winding Down of a Decade

Though the following year, 1978, saw no further increase in service, it did mark a change in the operational structure, as the corporate headquarters was relocated from Provincetown to Naples. However, the year will indelibly be remembered not for the accomplishments nor misfortunes of any individual airline, but rather, for a certain piece of legislation — one that forever changed the scope of commercial aviation: the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978.

With the onset of deregulation, new airlines, routes and destinations began springing up virtually overnight, catapulting the airline industry on its head. Though Old Man Van felt secure behind PBA’s solid and monopolized routes, this did not stop him from capitalizing on the current legislation, for in July 1979, the carrier introduced roundtrip service between Boston and the resort community of Hyannis, Massachusetts — the carrier’s first new Northern destination in 30 years.

While this newest route proved to be an initial success, it could not approach the fruition of the system’s leading city pair, Naples and Tampa. In fact, only one month prior, the CAB had recognized the Naples–Tampa run as the fifth busiest commuter route in the nation, as Naples Airlines was boarding between 150,000 passengers and 220,000 passengers annually between the two Gulf Coast cities.

As the 1970s began coming to a close, Old Man Van publicly announced his retirement from the airline. Though still in favorable health, it had always been his intention to work until age 60 and then retire. Therefore, with this milestone vast approaching, he thought it best to turn the company reins over to his sons at decade’s end. Thus, on Dec. 31, 1979, Old Man Van officially stepped down as the head of PBA.

A Changing of the Guard

On Jan. 1, 1980, a new dawn arose on Provincetown-Boston Airline. Having been appointed by their father, sons John Jr. and Peter took their respective places as the company’s new CEO and president. Yet, this did not spell the end for the senior Van Arsdale. When the time came for Old Man Van to retire he declined to do so, citing that the airline’s transition into the deregulated era was incomplete. Therefore, he agreed to stay on for one additional year at the position of vice president.

While Old Man Van indeed remained at the airline, it did not take long to realize just who was in command. In their first decree as acting management the brothers mandated that the organization be recognized under one identity — PBA. Hence, shortly thereafter all references to Naples Airlines quietly disappeared into obscurity. Yet, the Van Arsdales were only beginning to flex their newfound authoritative muscle.

Throughout their father’s tenure the brothers had been instilled the principle of playing it safe: operate monopolized routes while remaining relatively debt free. However, the Van Arsdale boys had now grown weary of their father’s conservative approach. Thus, they decided that a modernization of the fleet was in order and immediately began looking to purchase the carrier’s first turboprop airliner. In addition, they also decided it was time to test PBA’s strength in the deregulated market.

Deregulated Dog Fight

In February 1980, the Marathon (Florida) Chamber of Commerce approached the Van Arsdales in an effort to bring PBA to their community located in the Florida Keys. This request came following a major reduction in service by the city’s lone carrier, thus resulting in a 30 percent downturn in commercial traffic. And since the town’s economy depended on the tourist trade, this decline posed a huge problem for city leaders. Upon assessing the Marathon market the Van Arsdales believed, with a little stimulation, the operation could indeed become profitable. Moreover, city airport officials proposed an added stipulation which further sweetened the deal: PBA would be granted exclusive rights to the airport’s terminal facility. Without further hesitation — and with the city’s endorsement — the brothers agreed to initiate PBA service into what would become the carrier’s ninth destination.

While this latest endeavor seemed to be none out of the ordinary, the Van Arsdales would be doing so against their father’s commandment of only operating monopolized routes. However, this would only be half the battle, for PBA would be going head-to-head with one of the biggest players in the game — Air Florida: “The Darling of Deregulation.”

Under the premise of the Air Florida Commuter system, Air Florida would lease various regional airlines — primarily within Florida and the Bahamas — in order to serve markets deemed too small to support the carrier’s jet aircraft. In this instance not one, but two regional carriers — Ocean Reef Airways and Air Miami — serviced Marathon on behalf of Air Florida.

When the call came in from Marathon, Old Man Van had been away in Washington on business. However, upon his return the senior Van Arsdale became livid when learning of his son’s latest intentions. Thus, Old Man Van presented the brothers with the following ultimatum: either stop the expansion and conform to all of his wishes until Jan. 1, 1981, or redeem his stock in the airline and buy him out immediately. Needless to say the brothers chose the latter option, and in turn, Old Man Van officially retired on April 30, 1980.

With the groundwork having been established the Van Arsdales immediately took Marathon by storm: promotional gifts for townspeople, a flood of advertising, lower fares and more than doubling the frequency of service found in the competition. On March 1, 1980, PBA inaugurated service to Marathon with five daily roundtrips to and from Miami.

As with any fight for supremacy in the deregulated era, PBA and Air Florida battled tooth and nail: First came the usual undercutting in pricing, followed by a maneuvering in schedules to see which airline would come up first on the computer screens of travel agents. In the end, however, PBA’s quality of service and operating advantage would spell defeat for its adversary.

While Air Florida continually utilized 15- and 19-passenger aircraft (i.e., de Havilland Herons, Twin Otters and CASA C-212s), PBA’s wider assorting fleet allowed it to operate the right aircraft with the appropriate traffic demand, which also came in handy when executing the company’s policy of never turning away a passenger — even if it meant flying an extra segment with only one patron aboard. However, it was during the offseason that Air Florida truly felt the effects of this mixed-fleet strategy. With its summer load factors naturally down, PBA began serving Marathon solely with nine-passenger Cessna 402s, thus enabling the airline to cut its operating costs to over half that of the competition.

After enduring nearly a two year battle with PBA, in addition to combating a negative image throughout the Marathon community, officials at Air Florida officially conceded the market on Dec. 1, 1981, leaving PBA as the monopolized air carrier to the city. Yet, as the Battle for Marathon raged on, the Van Arsdale brothers continued in their “ambitious” approach toward running the airline.

The Ambitious Nature

On May 7, 1980, PBA announced an order for two, 19-passenger Embraer EMB-110P1 Bandeirantes, thus fulfilling the demand for the airline’s first turboprop. In addition, the airline also announced an order for five Embraer EMB-120 Brasilias, making PBA the launch customer for the type. Due for delivery in May 1985, the 30-passenger Brasilias were being purchased as a replacement for the carrier’s DC-3s.

Merely two months after placing the initial order, PBA debuted its brand new Bandeirantes on the Naples–Tampa run. Furthermore, by year’s end the airline would also add a third “Bandit” from Embraer, five more Cessna 402s, and its 12th and final DC-3.

When originally purchasing the Bandeirante, management had been guaranteed that an advanced version of the aircraft, one with a higher gross operating weight, would soon be available in the U.S. Under Special Federal Aviation Regulation Part 41 (SFAR-41), as prescribed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), this guarantee was fulfilled in the EMB-110P1/41, which debuted with PBA in June 1981. Shortly thereafter, PBA’s fleet of Bandits was modified to meet this higher operating standard.

In addition to these latest fleet acquisitions, a change in the airline’s operational structure also occurred during the year, having relocated the Northern base from Provincetown to the airline’s new facility in Hyannis. Furthermore, PBA also dubbed Key West, Florida, as its second, new destination of the year, with an introduction of service on Oct. 24, 1980.

While the overall operation appeared to be thriving, things were not as they seemed. With debt estimates as high as $2 million, it appeared the year’s immense expansion was breaking the corporate bank. On Dec. 31, John Jr. was working at his desk in Naples, still uncertain of PBA’s financial fate, when the yearly figures finally arrived: a $1.5 million profit on $12.5 million of total revenue. With a (successful) sigh of relief, the Van Arsdale brothers could now begin focusing on the future.

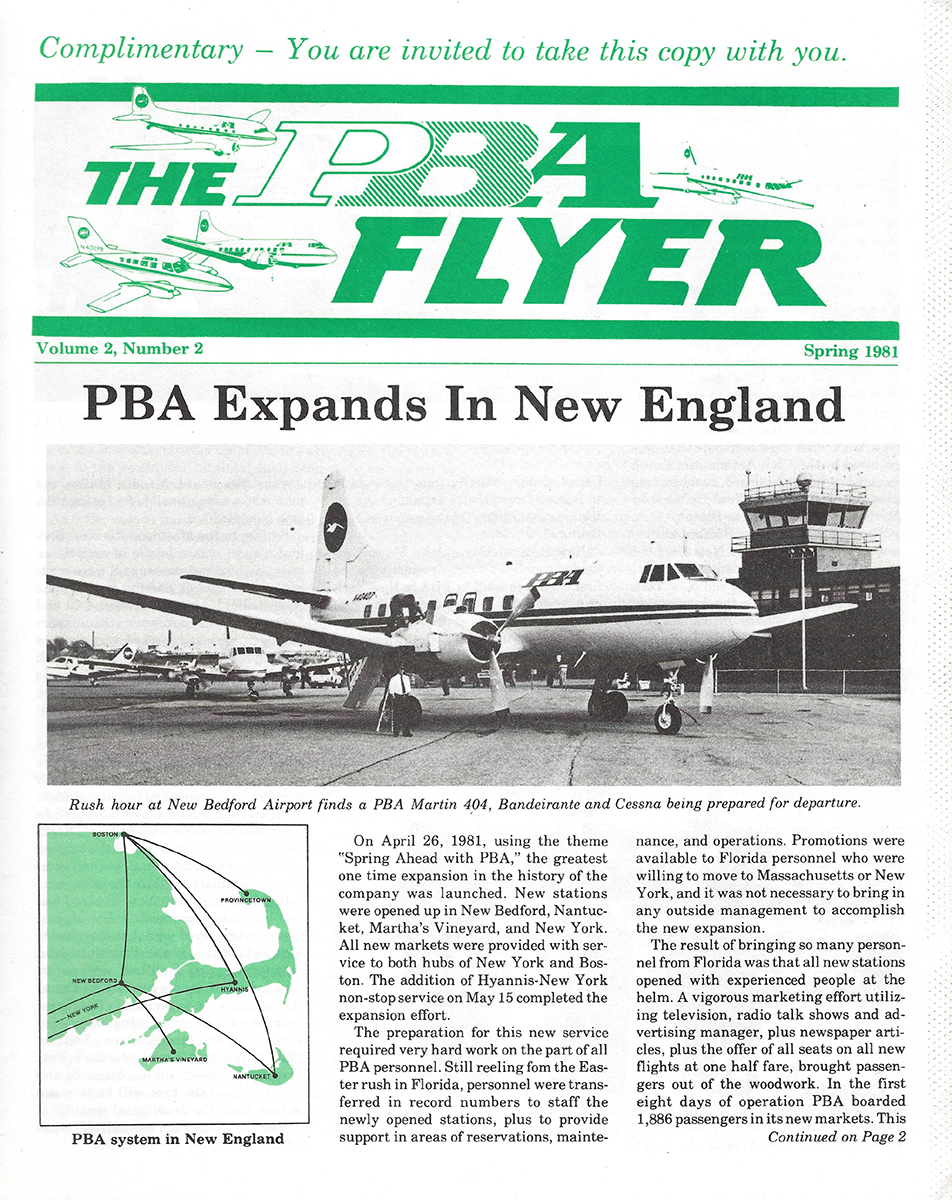

Icarus Takes Flight

On April 26, 1981, PBA initiated the greatest one time expansion in company history, having opened stations in the Massachusetts communities of Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket and New Bedford. Furthermore, service to New York’s La Guardia Airport also began on this same day, making the Big Apple the airline’s fourth hub destination. In addition, PBA also initiated service to the Florida cities of Fort Myers and Sarasota on Oct. 22 and Nov. 12, respectively. With six new destinations added throughout 1981, the carrier was now poised to supplement its fleet.

Prior to purchasing the Martin 4-0-4, management had originally set its sights on procuring the Convair 580; yet, with none available the Martinliner was selected. Now, six years later, another search was conducted for suitable Convairs and, once again, none were to be found. Inevitably, the Van Arsdales journeyed to the doorsteps of Piedmont Airlines, which by chance had a surplus of retired Nihon YS-11A-205s. With an excellent fleet of aircraft from which to choose, as well as a tremendous backlog of spare parts and maintenance support from Piedmont, PBA purchased four of the 58-passenger turboprops in April 1982. On June 18, 1982, PBA debuted the YS-11 as an unscheduled equipment substitution on the Nantucket–New Bedford route, and by June 27 all four aircraft could be seen in regular service throughout the airline’s Northern division.

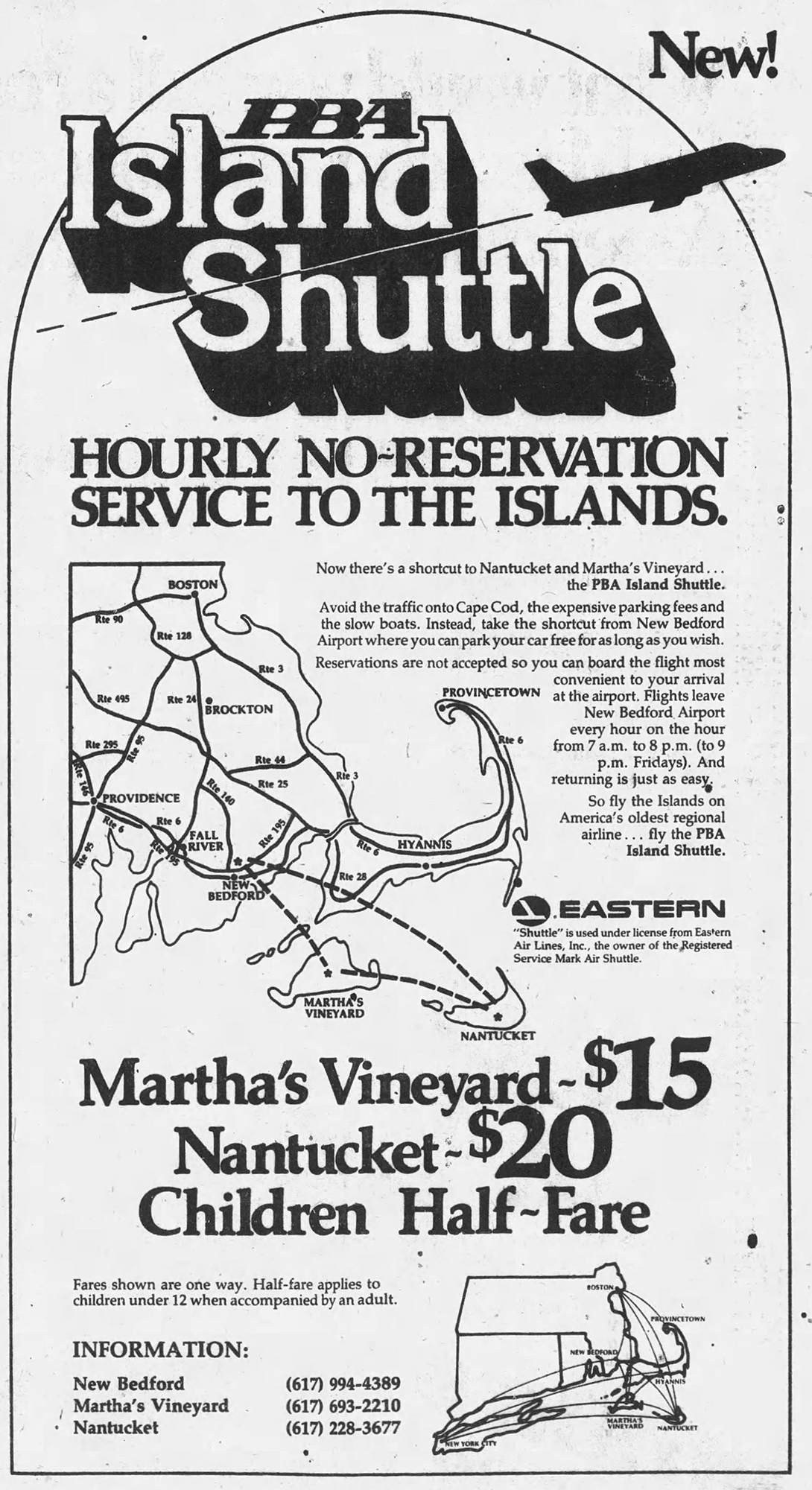

During the previous year’s expansion, management had also eyed the potential market between the New England mainland and the Islands of Massachusetts. In catering to vacationers known for spontaneously changing their plans, it was determined that a high frequency, low cost operation be incorporated — in which passenger reservations would not be required. On June 23, 1982, this vision came to be with the introduction of the PBA Island Shuttle.

Though seasonal in nature — operated initially between June 23 and Oct. 12 — the Island Shuttle was an instantaneous success. In addition, this newest endeavor also brought recognition from within the airline industry, as Air Transport World accorded PBA with the 1982 Market Development Award — an accolade never before bestowed upon a regional carrier.

While the year’s attention centered on the airline’s Northern division, two additional Southern destinations were also added to the system. In late October, PBA initiated seasonal service to the resort community of Ocean Reef, Florida, and then completed the year on a high note having launched service to the Florida state capitol of Tallahassee on Dec. 15, 1982.

Throughout the following year PBA continued to exercise its vast expansion efforts. On Feb. 1, 1983, the carrier started the ball rolling by inaugurating service to the Florida destinations of Pensacola and Jacksonville. Likewise, the cities of Orlando, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach, Florida, were also added on Oct. 15, Nov. 1 and Nov. 8, respectively. However, not to be outdone down South, Burlington, Vermont, joined the carrier’s growing list of markets on Oct. 23, 1983.

In addition to this increase in service, the year was also highlighted by the privatization of the airline. In a move to offset PBA’s indebtedness, 1.035 million corporate shares were sold for the first time — at an initial price of $10 per share — on Sept. 15, 1983. While the Van Arsdale brothers retained equal and controlling interest — each with a 33.67 percent stake in the company — the majority of the sale’s proceeds were used to pay off debt associated with the June acquisition of five ex-Pyramid Airlines YS-11s, as well as provide additional working capital.

Triumph & Tragedy

On Jan. 1, 1984, PBA ushered in yet another successful New Year. However, anticipation was running higher than usual, for the airline would be celebrating its 35th anniversary.

Commemorations aside, the year began in a favorable light for PBA: First, there was the elimination of rivals Trans East in New England and Dolphin Airways in Florida, as each airline declared bankruptcy in February — in turn, PBA acquired the assets of the latter carrier, including four additional Bandeirante aircraft. The windfall continued on May 1 with the disbanding of the Air Florida Commuter system, followed by the declared bankruptcy of parent Air Florida on July 3. With the competition left in its wake, PBA not only tightened its stronghold throughout Cape Cod and the Islands of Massachusetts, it also strengthened its prowess within the majority of the Florida market. Yet, while prosperity reigned midway through the year, the airline did endure two setbacks.

The first blow occurred in July as PBA suffered an accident: A Cessna 402 being ferried to Boston crashed during a foggy approach into Logan Airport. While the soloing pilot survived the ordeal the same could not be said for his wife — a lone, non-revenue passenger — who died in the accident. Then, on the evening of Sept. 7, PBA Flight 1042, also a Cessna 402, lost power in both engines shortly after departing Naples. With six passengers aboard, the sole pilot managed to set the crippled airliner down in a field approximately two miles from the airport. However, upon impact the twin Cessna immediately burst into flames, resulting in one fatality — the first in PBA’s history.

During an initial investigation of the latter accident, it was quickly discovered that the piston-engined Cessna had been incorrectly refueled with Jet-A — the lifeblood of jet and turboprop engines — instead of aviation gasoline (AvGas). Subsequently, the airline — and eventually the FAA — mandated that all fuel dispensing nozzles be of different shapes in order to alleviate any future mishaps.

Having rebounded from these tragic events, the airline took yet another bold step with the Oct. 5 purchase of Florida-based Marco Island Airways. With this latest acquisition under its belt, PBA not only enhanced its fleet of Martin 4-0-4s, it also added the five Bahamian destinations of Freeport, Treasure Cay, Marsh Harbor, Eleuthera and Rock Sound — not to mention the resort community of Marco Island, Florida. Thus, in addition to making its debut in the Bahamas, PBA could now showcase itself as an international carrier. Moreover, it was during this period that the world began taking notice of PBA’s success.

Over Expansion Looms at the Forefront

With an onward and upward drive toward becoming the nation’s leading regional carrier, the airline soon found itself a hot topic among such heavyweight publications as Inc., Flying and Business Week. Though most accounts portrayed the organization in a positive light, there was one issue that began filtering throughout aviation circles: PBA was in danger of over expansion. In fact, as of Nov. 1, the airline had begun serving yet another five destinations — Gainesville and Panama City, Florida; New Orleans, Louisiana; Charleston, South Carolina; and Savannah, Georgia — bringing the total to 11 new markets having been initiated 10 months into 1984, with three additional destinations yet to be opened during the remainder of the year.

While the expansion issue loomed in the forefront, the Van Arsdales were by no means oblivious to the matter. In an attempt to counter their naysayers, the brothers attributed their actions as simply the means to becoming Florida’s predominant regional carrier and that the situation was well in hand. Yet, it would take the airline’s third quarter operating results to assure any fears concerning the carrier’s immediate future.

America’s №1 Regional Airline

Before a gathering of airline employees on Nov. 7, John Jr. had the privilege of reporting the following operating results: As of Aug. 31, 1984, PBA was carrying 4,000 passengers daily — conducted on 500 flights, utilizing 104 aircraft (nine Nihon YS-11s, 11 Martin 4-0-4s, 12 Douglas DC-3s, 17 Embraer EMB-110s and 55 Cessna 402s) — between 36 cities in seven states and the Bahamas. As a result, the airline had boarded over 1.1 million passengers into the third quarter of the year. Furthermore, the carrier could expect to board 1.5 million passengers for the entire year, as well as a projected 2 million passengers throughout 1985. Thus, in addition to becoming the first commuter airline ever to board one million passengers in a single year, PBA had also become the leading regional airline in America.

Melted Wings: The Fall From Grace

Though much celebration rang throughout the organization, there was also cause for concern. Following the Sept. 7 crash in Naples, a former PBA pilot, Carlo Giammette, approached the FAA claiming to have copies of documentation falsified by airline personnel. Therefore, on Oct. 29, and with these newfound allegations in tow, the FAA launched into its third inspection of PBA for the year. Though the airline had ideally passed its previous inspections, the FAA now came armed with not only falsified records, but sworn affidavits from current PBA pilots whose testimony corroborated this information. While John Jr. considered the allegations a “vendetta” brought on by a disgruntled former employee — fired nearly two years earlier — he could only watch and wait as government inspectors turned the company inside and out.

By Nov. 9, allegations of wrong doing began filtering into John Jr.’s office. In turn, five of the airline’s top managers resigned their posts, leaving a hand full of executives and the Van Arsdales to face the music — though the wait would be short-lived. Merely one day later a final verdict had been rendered, and with it came the harshest penalty to be had by an airline: On Nov. 10, 1984, an Emergency Order of Revocation was ordered by the FAA. Thus, in addition to being grounded, America’s No. 1 regional airline had also been stripped of its operating certificate.

The charges against PBA involved a myriad of personnel ranging from pilots to mechanics, flight attendants and management. In all, over 160 violations were levied against the airline, including the following allegations:

- Multiple fraudulent or intentionally false statements involving proficiency and competency checks, in which the checks were never administered;

- Use of unauthorized personnel to perform aircraft maintenance;

- Improper training of flight attendants;

- Invalid proficiency checks, in which 35 pilots received approved checks from unqualified personnel;

- Exceeding the time limit for required inspections of aircraft;

- Use of unqualified inspectors (i.e., uncertified, untrained, unqualified and unauthorized personnel) who, during “numerous instances,” signed off on required maintenance items.

Migration Flight Spells Coup de Grace

The final straw came, however, with the discovery of falsified documents pertaining to one of PBA’s migration flights — a term coined to describe the airline’s operational shift between its Northern and Southern divisions. Throughout the month of May, in which Florida’s tourist season began winding down, a series of weekend flights would depart Naples en route to Hyannis. Loaded with additional personnel and office equipment, each aircraft would be ferried northbound in time for the summer season. Then, shortly after Labor Day, the same process would work in reverse in support of Florida’s winter season. As a means to offset the cost of this twice-yearly shift, the airline would exploit the capacity of its Martinliners and YS-11s by offering seats on the 1,200-mile journey. In turn, three or four such flights were operated during each migration period.

On Nov. 29, 1983, John Jr. was the pilot-in-command of a Martin 4-0-4 bound for Naples when, while en route to a refueling stop in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the Martinliner suffered a major loss of hydraulic fluid some 40 min. into the flight. Nevertheless, instead of immediately returning to Hyannis, as required by the FAA, Van Arsdale chose to continue on to Jacksonville, Florida, where PBA had an established maintenance base. Upon completing an otherwise uneventful flight the aircraft was immediately grounded, yet no mention of any mechanical failure was ever reported. Once in Jacksonville the passengers were then placed aboard the only available aircraft, a YS-11. However, since neither Van Arsdale nor his co-pilot held a type rating on the Japanese-built airliner, this flight would be flown illegally. Regardless, Van Arsdale eventually persuaded the co-pilot to join him on the final leg to Naples. Once there, Van Arsdale then forged the signature of a certified YS-11 pilot into the aircraft’s log book.

The FAA inevitably cited Van Arsdale for flying both the 4-0-4 and YS-11 “in a reckless manner that endangered the lives and property of others.” Moreover, additional violations included flying an “unairworthy” aircraft and authorizing a flight in the YS-11 by a non-qualified pilot. Consequently, on the same day of PBA’s grounding, Van Arsdale’s pilot’s license was revoked. Therefore, in lieu of the on-going controversy surrounding the airline and himself, John Jr. immediately resigned as chairman and CEO of the company. Now, if PBA was to survive, it would be done so with Peter Van Arsdale at the helm.

Picking Up The Pieces

Having assumed control of the company, Peter assembled the remaining executive members in order to contemplate the airline’s future. The board quickly discerned that with PBA’s operating certificate revoked the carrier would have to rebuild from scratch, as its 35 years of experience had now been rendered null and void. Thus, the airline would be obligated to rewrite its own manuals for each aircraft type, endure a reinspection of the entire fleet, followed by the retraining and retesting of each pilot — all under the watchful scrutiny of the FAA.

Under the plan to revitalize the grounded carrier, recertification would be sought on an incremental basis beginning with the smallest type aircraft. Throughout this process Team PBA — a once mighty force of 1,500 employees now reduced to 500 in number — worked virtually nonstop toward getting the airline back into business. Yet, while painstaking in nature, this diligence did not go unrewarded.

Merely two weeks after having been grounded the carrier was awarded a Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) Part 135 certificate authorizing its return to service — albeit only with its Cessna 402s. On Nov. 25, 1984, PBA — touted by the FAA as “the most inspected airline in America” — once again took to the skies.

Next on the airline’s agenda consisted of the recertification of its Embraer Bandeirantes. Having achieved this goal on Dec. 2, PBA immediately placed its Bandits back into service. Therefore, with the introduction of its second aircraft type, PBA had now returned to full service in less than a month after having been shutdown.

To this point — and to his credit — Peter Van Arsdale had achieved what many skeptics believed would be an impossibility. Yet, in addition to returning to full service the airline was also boarding 2,400 passengers daily, making it the nation’s third largest regional carrier. Though still faced with many provisions, Van Arsdale was elated over the recent turn of events. Unfortunately, however, all of his fruition would soon be for naught.

The Beginning of the End

On the evening of Dec. 6, 1984, PBA Flight 1039, an EMB-110, mysteriously crashed nearly two minutes after taking off from Jacksonville, killing all 11 passengers and two crew members aboard. By all accounts Flight 1039 began in an ordinary fashion. At 6:15 p.m., and with clear skies and a reported visibility of seven miles, the Brazilian-built commuter made a seemingly uneventful departure. However, upon climbing to an altitude of approximately 500 ft., the Bandeirante — making its fourth roundtrip of the day between Jacksonville and Tampa — suddenly spun out of control, plummeting into a nearby wooded area.

Merely minutes after the disaster, Peter received the news while working at his office in Naples. There, a stunned Van Arsdale began contemplating a rationale for this recent accident. Though unable to pinpoint a specific reason, Peter consequently ordered an immediate grounding of the carrier’s Bandeirantes.

By Dec. 9, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) was ready to announce its preliminary findings, as investigators quickly discerned that the plane’s horizontal stabilizer had broken off shortly into the doomed flight. Hence, the crash was attributed to a design flaw and not the airline. In turn, government officials ordered a nationwide grounding of the Bandit pending a modification to the tail assembly.

Though exonerated of any blame for the accident, the damage brought on by public backlash was already complete. Literally overnight company stock began tumbling, while reservations fell by 75 percent. Even the backing of the FAA — which made a concerted effort to clarify any misconceptions regarding PBA — was not enough to counterbalance the negative image cast upon the carrier.

With customer confidence continuing to wane, Peter remained undaunted in his attempt at resurrecting the family business. By Dec. 20, it appeared that PBA’s fortune was beginning a turnaround. With the introduction of its DC-3s the carrier was now poised to attain its Part 121 certificate, and with it the reemergence of its Martin 4-0-4s and YS-11s. However, even this bit of prosperity turned into a boondoggle. On Dec. 27, a PBA DC-3 was forced to make an emergency landing in Fort Myers, Florida, after it was discovered that the gust locks had not been removed from the aircraft’s tail prior to departure. Though non detrimental in nature, this potentially hazardous incident — involving the airline’s most senior pilot — was yet another black mark against the organization.

A New Lease on Life

In the months shortly following this latest debacle, and with bills piling up and creditors at the door, Peter felt he had no choice but to place the airline up for sale. Among the potential buyers was prominent Tampa business man, attorney and owner of pro football’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Hugh Culverhouse, who guaranteed a $1 million bank loan in exchange for a six month warrant to buy 500,000 common shares of unissued stock at $2 per share. Furthermore, in addition to gaining control of the organization, Culverhouse would also obtain a two-year option to purchase the 2.2 million shares (i.e., controlling interest in the company) from John Jr. and Peter Van Arsdale. On Feb. 1, 1985, this transaction was made official as Culverhouse appointed C. Bill Gregg, a former Eastern Airlines executive, as PBA’s new chairman of the board and CEO. In turn, Peter resumed his former role as company president.

All was not lost, however, for on May 17 PBA regained its Part 121 status enabling the carrier to operate its larger aircraft. While the Martin 4-0-4 appeared to be the next type destined for recertification, the airline decided to forego the classic Martinliner in favor of the more economical and passenger appealing YS-11. Consequently, the carrier’s 4-0-4s never resumed service.

With four aircraft types now aloft, including the modified Bandeirante, PBA looked to regain its prominence and emerge from under the cloud of bankruptcy. However, as had been the case in recent times, just when there appeared to be a light at the end of the tunnel, it turned out to be an oncoming train.

With PBA’s destiny in dire straits it did not take long for the competition to go in for the kill. And though the ailing carrier battled with much diligence, the opposition quickly introduced a new player to the game — jet aircraft. During the summer of 1985, New York Air initiated DC-9 service into PBA’s tried and true New England destinations. In October, Piedmont Airlines then followed suit, having introduced the Fokker F.28 to Florida on its new intrastate service, the Piedmont Shuttle. In both cases PBA’s ridership fell even further as the airline’s propeller-driven aircraft were no match against their jet-powered contemporaries.

The Close of an Era

In December of that same year, 1985, and with the airline’s debt reaching staggering proportions, Culverhouse withdrew from any further assistance toward PBA. In turn, Peter Van Arsdale resumed his role as the head of the airline, and immediately began courting potential suitors for the financially stricken carrier. In February 1986, Newark, New Jersey-based People Express turned out to be PBA’s deliverer. With permission from the Florida bankruptcy court, the low-cost innovator provided PBA with a much needed cash loan, while at the same time began working on a reorganization plan in order to acquire the commuter. In May of that same year, People Express inevitably purchased the ailing carrier for a sum totaling $30 million: $2 million for the purchase of the airline, $700,000 for the previously mentioned loan, and the remainder going toward reimbursing creditors — a move which maneuvered PBA from under Chapter 11.

Having assumed the role of parent company, People Express began operating its latest acquisition as a feeder line for its system network. As a result, PBA’s Northern division was reinstituted around People Express’ Newark hub. And in a similar manner, the carrier also abandoned its successful Tampa hub in a move to neighboring St. Petersburg — People Express’ destination for serving the Tampa Bay area.

However, in December 1986, it was announced that People Express, including its subsidiaries (Frontier Airlines, Britt Airways and PBA), was being acquired by the Texas Air Corporation. On Feb. 1, 1987, the no-frills giant was officially folded into Texas Air’s Continental Airlines division, and in turn PBA joined the ranks of Continental Express. Merely three months later PBA was then purchased by Maine-based Bar Harbor Airways — another of the many airlines making up the Texas Air conglomerate — which operated under the dual monikers of Continental Express and Eastern Express.

With the purchase of PBA, Bar Harbor now focused its efforts toward Continental’s Northeastern operations, as PBA’s Florida system was quickly deemed expendable. Therefore, on May 1, 1987, PBA — with the exception of the highly profitable Miami–Marathon route — ceased all operations within the state of Florida.

By the summer of 1988, however, this halt in service proved to be temporary, for PBA had indeed returned to the Sunshine State, albeit in the unfamiliar blue and white livery of Eastern Express. In the meantime, a plan for modernizing Bar Harbor’s fleet was also well underway, in which PBA’s antiquated aircraft would be retired in favor of the sleek new turboprops (i.e., the Saab 340, ATR-42 and Beech 1900) on the market. Sadly, since this undertaking would denote an end to PBA’s fleet, it was decided that the carrier’s operating certificate also be retired.

On Sept. 6, PBA Flight 2260, a DC-3 en route from Nantucket to Hyannis, was seen rocking its wings during a flyby prior to landing: a sentimental goodbye gesture on PBA’s final flight, performed on none other than N136PB (“Old 36”) — then the world’s highest time aircraft — with 91,402 total hours — and the pride of PBA’s fleet. The following day, Sept. 7, 1988, marked the close of an era as PBA’s operating certificate was officially retired, thus ending a legacy of nearly 40 years of regional airline service.

Postscript

Shortly after Bar Harbor’s acquisition of PBA, Peter Van Arsdale retired from the airline business in June 1987. In turn, he began a successful chain of travel agencies throughout the Naples area. John Jr., on the other hand, inevitably returned to the airline industry as, ironically, marketing director for Bar Harbor Airways. Thus, a Van Arsdale was involved with PBA to the very end. Eventually, however, he, like his brother, retired from aviation to become a successful businessman within the Naples community.

Though having officially retired in 1980, Old Man Van never really left the airline, nor the industry. Whether it be editing the company newsletter or offering his expertise, he could always be seen acting in some capacity at PBA, which, according to John Jr., “was not really work, but a labor of love.”

Following the airline’s demise Old Man Van went on to join the board of directors at Cape Air — a Hyannis-based commuter — in 1990. In the years that followed he enjoyed life to its fullest until eventually succumbing to cancer on Feb. 7, 1997.

Throughout his 77-year lifetime John Van Arsdale Sr. was able to behold many changes within the realm of aviation. Yet, not only did he witness the evolution of commercial flight, he also played a major role in its development. A pioneer of the regional airline industry, Provincetown–Boston Airline will forever live on as a monument, having helped pave the way for commuter airlines past, present and future.

Two years later good fortune again intervened on Van Arsdale’s behalf, as leaders from the nearby community of Provincetown, Massachusetts, requested that he open a similar venue at the town’s new airport. Sensing a great opportunity, as well as realizing the G.I. Bill would not last forever, Van Arsdale seized the moment. Though the Provincetown Municipal Airport officially opened on Oct. 19, 1948, a double ceremony was held at the facility on Oct. 31: one celebration commemorated the airport’s grand opening, while the other marked the debut of the field’s first tenant, the (newly relocated) Cape Cod Flying Service.

Two years later good fortune again intervened on Van Arsdale’s behalf, as leaders from the nearby community of Provincetown, Massachusetts, requested that he open a similar venue at the town’s new airport. Sensing a great opportunity, as well as realizing the G.I. Bill would not last forever, Van Arsdale seized the moment. Though the Provincetown Municipal Airport officially opened on Oct. 19, 1948, a double ceremony was held at the facility on Oct. 31: one celebration commemorated the airport’s grand opening, while the other marked the debut of the field’s first tenant, the (newly relocated) Cape Cod Flying Service.

On Nov. 30, 1949, PBA’s maiden flight — touting a fully loaded Cessna Bobcat — departed Provincetown promptly at 9 a.m., arriving at Boston’s Logan Airport 25 minutes later.

On Nov. 30, 1949, PBA’s maiden flight — touting a fully loaded Cessna Bobcat — departed Provincetown promptly at 9 a.m., arriving at Boston’s Logan Airport 25 minutes later. Though financially sound since its inception, PBA’s seasonal service always presented an unequivocal dilemma: both the airline’s fleet and personnel were being underutilized during the winter off-season. In an attempt at resolving this problem, Van Arsdale and his wife traveled to the state of Florida, also renown for its tourist industry.

Though financially sound since its inception, PBA’s seasonal service always presented an unequivocal dilemma: both the airline’s fleet and personnel were being underutilized during the winter off-season. In an attempt at resolving this problem, Van Arsdale and his wife traveled to the state of Florida, also renown for its tourist industry.

Modeled after Eastern Airlines’ famed Air-Shuttle, PBA’s Island Shuttle — a name implemented only after receiving permission from interline partner Eastern — commenced with hourly service between the mainland destination of New Bedford and the Islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Shortly afterward, Shuttle services were increased having added the Hyannis–Nantucket route on July 1.

Modeled after Eastern Airlines’ famed Air-Shuttle, PBA’s Island Shuttle — a name implemented only after receiving permission from interline partner Eastern — commenced with hourly service between the mainland destination of New Bedford and the Islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Shortly afterward, Shuttle services were increased having added the Hyannis–Nantucket route on July 1.

Having assumed control of the company, Peter assembled the remaining executive members in order to contemplate the airline’s future. The board quickly discerned that with PBA’s operating certificate revoked the carrier would have to rebuild from scratch, as its 35 years of experience had now been rendered null and void. Thus, the airline would be obligated to rewrite its own manuals for each aircraft type, endure a reinspection of the entire fleet, followed by the retraining and retesting of each pilot — all under the watchful scrutiny of the FAA.

Having assumed control of the company, Peter assembled the remaining executive members in order to contemplate the airline’s future. The board quickly discerned that with PBA’s operating certificate revoked the carrier would have to rebuild from scratch, as its 35 years of experience had now been rendered null and void. Thus, the airline would be obligated to rewrite its own manuals for each aircraft type, endure a reinspection of the entire fleet, followed by the retraining and retesting of each pilot — all under the watchful scrutiny of the FAA.